What Is Washi?

-

The Origin of Washi

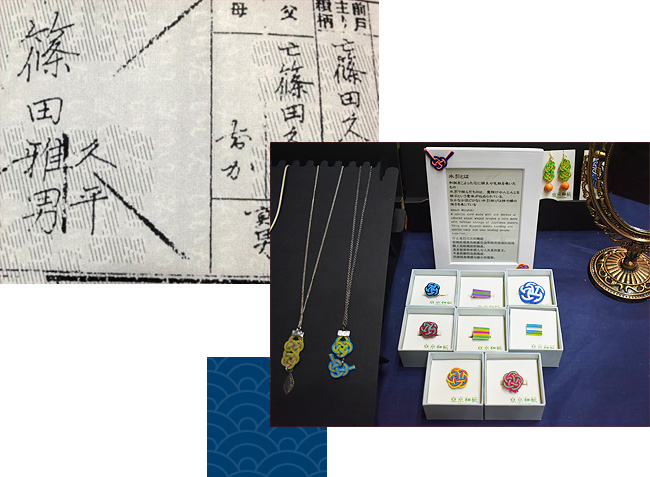

Paper was created in China in the 2nd century. B.C. The technique was brought from China to Korea, and to Japan by a monk from Koguryo (ancient Korea), Doncho in the Era of Empress Suiko (610 A.D.). Paper was mainly used to write family registrations and to copy Buddhist scriptures on. It was so precious that it was recycled and reused. The oldest washi has a family registration in 702 and it is preserved in Shosoin in Nara.

-

The Origin of Washi

*Kozo -> Washi is made from barks of trees. Kozo is a type of deciduous mulberry shrub, which is characterized by its long, thick, and strong fibers. It is harvested during December and January, then cut into same lengths and steamed. After steaming, it is divided into the core and the bark to make washi. Washi is made from only “shirokawa” (white bark), which is stripped of its outer bark, onikawa and amakawa. This means just a small amount of paper can be produced from a tree (Only about 5% of the raw wood weight).

-

Plant

*Tororo aoi (Sunset muskmallow) The tororo aoi plant is in the Malvaceae family. It is also called Hana Okra because its flowers are similar to the ones of Okra. It produces a mucilaginous material when its roots are beaten, and this material (called neri) is mainly used for papermaking. Neri plays an important role to degrade kozo fibers equally under water (If it is only water, fibers sink to the bottom). The mucilaginous material is not extracted from the whole root but only from its bark (There is a hard core at the center of the roots, which does not produce the substance).

Process

Harvesting kozo trees (kozo is deciduous shrub).

The harvesting time is during December and January

Cutting the branches into the same length and steaming (about 3 hours).

After steaming, dividing into the core and the bark.

Harvesting kozo trees (kozo is deciduous shrub).

The harvesting time is during December and January

Cutting the branches into the same length and steaming (about 3 hours).

After steaming, dividing into the core and the bark. Stripping onikawa (the 1st bark layer) and amakawa (the 2nd) with a spatula to get sirokawa.

(Washi is made from the shirokawa of kozo.)

This process is also called “kazuhiki” or “hyohitori”.

Stripping onikawa (the 1st bark layer) and amakawa (the 2nd) with a spatula to get sirokawa.

(Washi is made from the shirokawa of kozo.)

This process is also called “kazuhiki” or “hyohitori”. Bleaching shirokawa naturally by placing it in water.

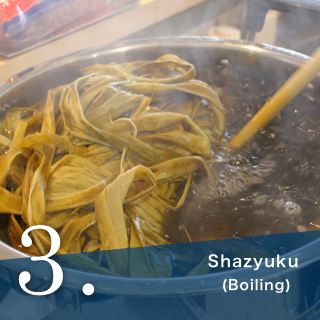

Then boiling it in a pot (about 3 hours) to pick out only pure fibers.

(Adding soda ash to remove impurities and to soften the fibers.)

After that, placing the fibers in water again to remove the lye.

Bleaching shirokawa naturally by placing it in water.

Then boiling it in a pot (about 3 hours) to pick out only pure fibers.

(Adding soda ash to remove impurities and to soften the fibers.)

After that, placing the fibers in water again to remove the lye. Removing impurities and flaws from the shirokawa.

Removing small “chiri” (dust) from each fiber carefully.

This process is also called “chiriyori”.

Removing impurities and flaws from the shirokawa.

Removing small “chiri” (dust) from each fiber carefully.

This process is also called “chiriyori”. Beating shirokawa with a wooden stick to untangle the fibers.

These disentangled small fibers are called “kamiso” (the source of paper).

How much disentangled the fibers are becomes clear when they are put in water.

Recently, this process is sometimes done with a machine.

Beating shirokawa with a wooden stick to untangle the fibers.

These disentangled small fibers are called “kamiso” (the source of paper).

How much disentangled the fibers are becomes clear when they are put in water.

Recently, this process is sometimes done with a machine. Neri plays an important role to degrade kozo fibers equally under water.

(If it is only water, fibers sink to the bottom).

Using a mucilaginous material extracted through beating the roots of the Troro aoi plant.

Neri plays an important role to degrade kozo fibers equally under water.

(If it is only water, fibers sink to the bottom).

Using a mucilaginous material extracted through beating the roots of the Troro aoi plant. Putting the beaten shirokawa and neri into sukibune (paper-manufacturing container) and stirring them.

The process of suki is spreading out the shirokawa fibers in water flatly on “su” (the mat made of split bamboo, reeds, and silk thread tied together), which is put between “keta” (the wooden flame).

There are various ways to make paper, such as nagashizuki, tamezuki, nagashikomi, etc.

Washi contains some water right after being made and this state is called “shitogami” (wet paper).

Then placing shitogami one by one.

This piled up state is called “shito” (the paper bed).

Putting the beaten shirokawa and neri into sukibune (paper-manufacturing container) and stirring them.

The process of suki is spreading out the shirokawa fibers in water flatly on “su” (the mat made of split bamboo, reeds, and silk thread tied together), which is put between “keta” (the wooden flame).

There are various ways to make paper, such as nagashizuki, tamezuki, nagashikomi, etc.

Washi contains some water right after being made and this state is called “shitogami” (wet paper).

Then placing shitogami one by one.

This piled up state is called “shito” (the paper bed). Sandwiching and pressing shito with a compressor to wring out its water.

Then peeling each shitogami off and putting it on a board with a brush to dry naturally.

(Neri makes it possible to peel piled up paper off cleanly.)

There is another way to dry paper, like putting it on a hot iron plate.

When it is dried, it is then inspected for flaws and dust.

Now it’s all done!

Sandwiching and pressing shito with a compressor to wring out its water.

Then peeling each shitogami off and putting it on a board with a brush to dry naturally.

(Neri makes it possible to peel piled up paper off cleanly.)

There is another way to dry paper, like putting it on a hot iron plate.

When it is dried, it is then inspected for flaws and dust.

Now it’s all done!

What is Mizuhiki?

- Mizuhiki (literally “Water-pull”) refers to a Japanese traditional cord tightly wound and starched with ilk thread or colored paper. It’s said that mizuhiki is originated around 1330. They were twines in red and white made as dedication to the powers. It was then transformed to a paper form. In 1900s, mizuhiki was very much treasured as bundles for documents and hair. Nowadays, it’s mainly used as the decoration on the shugi (ceremonial money) envelope to enclose money as well as wishes and thoughts. In Japan, envelopes with mizuhiki is used in ceremonies. Why Mizuhiki is used in ceremonial occasions in Japan? It’s commonly believed that Mizuhiki works as bai sema to drive away evils for the establishment of a holy zone.

- Generally speaking, there are two main categories in mizuhiki. The first one is “Musubikiri”, which is very hard to unknot. It symbolizes “a strong bonding and connection”. It looks like a whirlpool that is basically done by “Awaji knotting”. It can be further elaborated to become more sophisticated ones like umemusubi (plum knots) and matsumusubi (pine knots). The second one is “hanamusubi”, which can be unknotted by pulling the two tails. Sometimes it’s named as “butterfly knot” too. As it can be knotted repeatedly, it is a symbol of having luck and happiness multiple times in life. It is commonly used in celebration of new lives and moving.

-

The importance of the number

The number of the paper thread is important as well, which is normally 3, 5, or 7. By using an odd number that can’t be divided, the wish of “bonding strongly without being separated” is embedded.

- Tokyo Washi has been running its mizuhiki business in Iida-shi, Nagano until the generation of the grandfather of the current president, Shinoda. However, the store was closed after the sudden death of the grandfather (about 90 years ago). With an aim to promote the traditional mizuhiki created by ancestors, mizuhiki from Iida-shi, Nagano is used in this product. Mizuhiki also links to the ladies living in Ishinomaki-shi, Miyagi- the devastated area of Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. It doesn’t merely help to rejuvenate the cities but to bridge up and link up Tokyo and these cities through the ever-spreading washi paper.